QUINCEAÑERE: 15 años de DiabloRosso

Curated by Pablo León de la Barragroup exhibition

nov 27 / 2021 - feb 26 / 2022

nov 27 / 2021 - feb 26 / 2022

Sandra Eleta, Fabrizio Arrieta, Engel Leonardo, Juan Pablo Garza, Katherine Bernhardt, Pia Camil, José Lerma, Donna Conlon & Jonathan Harker, Hellen Ascoli, José Castrellón, Federico Herrero, Luis Camnitzer, Adán Vallecillo y Sol Calero

Photos: Raphael Salazar

Wallpaper Design: Priscila Clementti

Historic Investigation: Paulina León

A conversation between Johann Wolfshoon and Pablo León de la Barra

PLB: Johann, I wanted us to start the conversation on how DiabloRosso gallery started; where did the idea of opening a gallery of contemporary art in Panama come from 15 years ago? Were there other art galleries at that time?

JW: Honestly, the starting idea back then wasn’t to create an art gallery. DiabloRosso was born as a space that sought to fill some gaps that we had in Panama, according to the five partners who founded the project: Analida Galindo, Carlos Ucar, Miky Fábrega, Rafa Arrocha and myself. The project started out at first as a concept shop and café, with an independent film and art gallery side to it. The shop showcased everything from avant-garde fashion made in Copenhagen to design, jewelry and decoration items, produced locally and abroad. It was a concept store before the term was coined.

The café boasted a short but wonderful menu, conceived by chef Clara Icaza, and with some of the best names given to dishes in all of Panama. In this space, we had screenings of independent cinema every Tuesday, with a careful selection of films. We did that for 8 years, every single week. When we first started these “dinner-screenings”, it was hard to find an audience, but as time passed, a crowd of regulars began to show up every week, making dinner reservations mandatory after a while. This showed us that it is possible to build audiences from the ground up, which encouraged us to continue with the gallery to this day.

The gallery emerged within the café and was a wholesome part of it. It filled the walls and, in some cases, changed the space. The vision we had for that space was much less international than the rest of the project. It was meant to be mainly a platform for local artists, whom we thought had plenty of talent, but not enough opportunities. We created a humble space, with the basic conditions to exhibit, and there we hosted concerts, talks, performances, etc.

In 2006, Panama had three contemporary art galleries with regular programming: Mateo Sariel, Allegro and Arteconsult, the latter being the most interesting one historically. Its founder Carmen Alemán had lived in New York and had contacts and resources that allowed her to bring some great Latin American artists to Panama. Out of those three, only Mateo Sariel is still open today.

PLB: What was the artistic, but also socio political context in Panama when DiabloRosso opened?

JW: When DiabloRosso opened in 2006, Panama was going through an economic momentum never seen before. That was the year that we had the referendum that approved the expansion of the Panama Canal. The climate was favorable and optimistic enough to throw the project out there, even though it made no sense in a way. We were living under a stable government, with a growing economy and solid public investment. Unemployment rates were declining, which contributed to a peaceful social climate. We experienced this growth until 2014, when everything started to change, mostly on account of issues related to state corruption. Panama has always been a hotbed of multiculturalism with a diverse population due to its transitional nature. But it has also suffered from pressing issues of wealth distribution and an extremely weak public education system, which only feeds into the cycle of poverty.

To give you some context, in Panama we had a couple of initiatives that had been profoundly interesting for the art scene: between 1993 and 2002 the weekly supplement Talingo (edited by Adrienne Samos and Alberto Gualde) was published in La Prensa, the country’s most widespread newspaper. Talingo featured articles on cinema, art and culture; whereas Mogo magazine (2000-1) offered a fresh perspective on the city and its dynamics. Founded by a group of artists and designers (Walo and Gustavo Araujo, Miky Fábrega, Jonathan Harker and Dany Silvera), it argued that “the official Panama is nothing but a lie that is believed because it is repeated too much”. Revolver (2001-2003) led by graphic designers Peter Novey and Ricky Salterio, was a visual and spirited editorial portfolio; and in 2003 Ciudad Múltiple happened, a city-wide exhibition initiative built around Panama City itself. Co-directed by Adrienne Samos and Gerardo Mosquera, it was a significant boost for a new generation of artists and left a mark on the lives of those who had the chance to interact with the project. An art biennial also took place regularly, after starting out as a painting contest originally, but with a structure that was in constant evolution. Shortly after DiabloRosso’s opening, its very last edition was produced, curated by Magalí Arriola and thematically focused on the Canal Zone.

In reality, ever since the beginning of that decade, Panama was experiencing a slowdown in contemporary art and cultural life in general. Beyond the idea of being a solution to a problem, DiabloRosso hoped to become a channel that enabled a new generation to explore new ideas and paths.

PLB: Can you talk a bit about the first exhibitions? How was the reception of the gallery in its context back then?

JW: We inaugurated the space with the first gallery show by Cisco Merel. After that, we had several group shows and open calls for the first few years, with some solo exhibitions here and there. It was a frenzy, there was a new exhibition every month! I was 26 when we opened the space, and every partner had their own ideas and energy, which we all brought to the table.

Locally, it was very interesting. We invented exhibitions that didn’t make much sense and invited established local artists to participate. For example, we had an exhibition for which every artist was given a toilet lid made of wood to use as the starting point for an artwork (Dada-ístmo, 2007). Another time, we did something similar with wooden chairs (Sunny & Chair, 2008); and we also gave disposable cameras to a number of public figures and intellectuals so that they could document their surroundings (Show me yours: Tu lugar favorito, 2010). We made open calls, with paper as the medium, to give the audience the possibility to easily interact with the space. The results were always fun and the conversations it generated were very uplifting.

PLB: At some point Diablo Rosso started looking beyond Panama and showing artists from abroad. How did that process happen? Who were those artists? I remember we met around 2008, back when I was the artistic director of a gallery in London and a member of the Gallery Committee of Zona Maco fair in Mexico, and you emailed me to introduce the gallery’s project.

JW: We met in person back in 2009, during Zona Maco’s “swine flu” edition. You were a member of the jury that selected the galleries in the New Proposals section. I remember we had our booth entirely painted in pink, full of works (mostly painting), which at that time in Mexico was unimaginable, and probably the worst idea in the world. I think the only other painting in all of the fair was a huge Federico Herrero work that you were showing. I recall that, courteous as we were, we walked up to you and introduced ourselves to thank you for having picked our gallery. Honestly I don’t remember if we had a long conversation, or if you saw something that could catch your interest in what we were showing (probably the pink walls!), but the following year you invited us to participate in a section that you were curating in Circa, Puerto Rico. You tapped us alongside five other young galleries (in a project called Somewhere Over the Rainbow, featuring Proyectos Ultravioleta from Guatemala City, Revolver from Lima, Proyectos Monclova and Preteen from Mexico City and Beta-Local of San Juan). There we actually got to know each other, we hung out a lot and you must’ve liked us, because even though our booth there was even worse than the one we had at Maco, we’ve been friends ever since.

It was then that we really started looking outwards at DiabloRosso. The links we had established at the fair and the comradery that we enjoyed have been the base for all that we’ve done, or tried to do from that moment on. Since 2012 our exhibitions have been mostly international: the first we did was organized with the girls of La Central, who were unable to participate in Circa due to visa problems. In that show, we had Federico Herrero, Pia Camil and Carolina Caycedo, to name a few. At the beginning of the year we organized an exhibition curated by Emiliano Valdés, Me asusta pero me gusta, which primarily focused on Guatemala, with the participation of Stefan Benchoam, whom we had also met at your project for Circa… We often repeated that type of dynamics, especially with Proyectos Ultravioleta, led by Stefan Benchoam, whom we grew very close to.

PLB: What I really was interested in back then when I invited you to Puerto Rico, was that young artists and spaces across the continent got to know each other and connected. I was aware that there were plenty of convergences between cultural, urban and political and economic contexts, as well as similar colonial and modern historical backgrounds; however, they barely knew about each other. The internet wasn’t what it is today, Facebook was taking baby steps, Instagram didn’t exist, and generally we were all gazing towards New York or Europe, instead of looking at ourselves. I think that what happened next was fascinating, a process of exchange, of getting acquainted and learning from each other. On the basis of our friendship, I visited Panama City quite a couple of times in the past few years, the first time in April 2010 I came out of curiosity, because I wanted to see where DiabloRosso existed. I returned in January 2013 as a speaker in the framework of the Central American Biennial, BAVIC. Later that year, I came back in November to visit Sandra Eleta in Portobelo as well as Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker in Panama City, prior to acquiring their masterpiece Drinking Song for the collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The last time I was here was in August 2017 to visit Sandra Eleta and chat about the pictures that she had made of Ernesto Cardenal and Solentiname, which I included in an exhibition on Solentiname at New York University and at Museo Jumex in Mexico City. Truth is, I would’ve loved to come more often, especially since I have so many connections in Panama, and that’s something that I would definitely do if Copa Airlines’ Stopover program wasn’t so expensive. In all the times I’ve stayed here, I’ve always been impressed by Panama’s schizophrenic situation: on one hand, the amount of skyscrapers under construction, which seemed to boast an accelerated economy; and on the other a sort of cultural desert, where despite there being a Museum of Biodiversity designed by Frank Gehry and a Museum of Contemporary Art, the latter seemed until recently to be in hibernation. It looked as if there was much being built, but what exactly was getting built seemed unclear and misunderstood, not to mention the fact that culture is a fundamental part in the construction of a mature society. Panama could be, based on its economy, location and the fact that it is an airline hub, a major cultural center in the region with a museum to match. Yet, if the money seems to be there, and in abundance, government or private support to culture and the arts don’t quite measure up to it.

If I’m not wrong, it also looks like there is a cultural void, in which the older generation hasn’t quite been capable of interacting with a newer generation of artists and cultural practitioners. Maybe I’m exaggerating, but Panama City would have the possibility of being what other city-states such as Sharjah, Dubai, Qatar or Singapore are to their regions, and having a cultural scene, a museum or cultural center and/or a biennial up to the task. In this context, it is incredible that a project like DiabloRosso has managed to exist and contribute to its cultural scene for 15 years, and this is precisely what this exhibition celebrates. In Central America and the Caribbean, specifically, it is maybe a unique case alongside Proyectos Ultravioleta in Guatemala City. DiabloRosso has been a valuable asset in the exhibition and connection of artists from Central America and the rest of the continent, in a way in which few galleries in Latin America have excelled. As a part of the research made for this exhibition, it also becomes clear how much DiabloRosso has matured throughout the past 15 years. This show Quinceañere celebrates these first 15 years, featuring works by some of the artists that have contributed to the development of DiabloRosso, but also certain shortcomings, like a minority of women artists in a predominantly male programming. I also feel that in the future it would be important that DiabloRosso show more Indigenous and Afro-Descendant artists (both communities that are very present in Panama’s racial and ethnic complexity) something that we also endeavored to include in this exhibition, but due to logistical complications, couldn’t do in the end. In the beginning, the idea behind this show was very simple: to invite 15 artists, one per year of existence, that at some point in its history had shown at DiabloRosso. In times of a pandemic and through the confinement that we are experiencing, I also wanted this show to be a party, and instead of using its budget to pay for the shipping of the works, it be allocated to funding these artists’ trips to Panama, so that they could each bring a work as a “present” to celebrate. The pandemic also made this difficult to achieve, as borders never fully reopened and traveling became increasingly challenging, making it also hard to define a date for the project. I also thought we could invite artists to produce a work for the anniversary and “fold” them into an envelope to ship them via FedEx, as a wink to Eugenio Dittborn’s postcard paintings. We ended up having to work with what we had, finding the way to make the pieces get to Panama in time for the 15th anniversary celebration, and to have all of them come together in the exhibition space as if shaping a cadavre exquis, in which each piece communicated the artist’s aesthetic interests. But also forming an energy field to honor the history of the gallery, nodding to future possibilities of dialog, action and thought for its future. The main exhibition space is also entirely painted in pink, which recalls the gallery’s booth at Zona Maco back in 2009, and also reminds me of the fact that I thought that rosso meant pink instead of red, as I’m not familiar with Italian. It’s also a playful allusion to the pink cakes and pastel-colored dresses worn by quinceañeras.

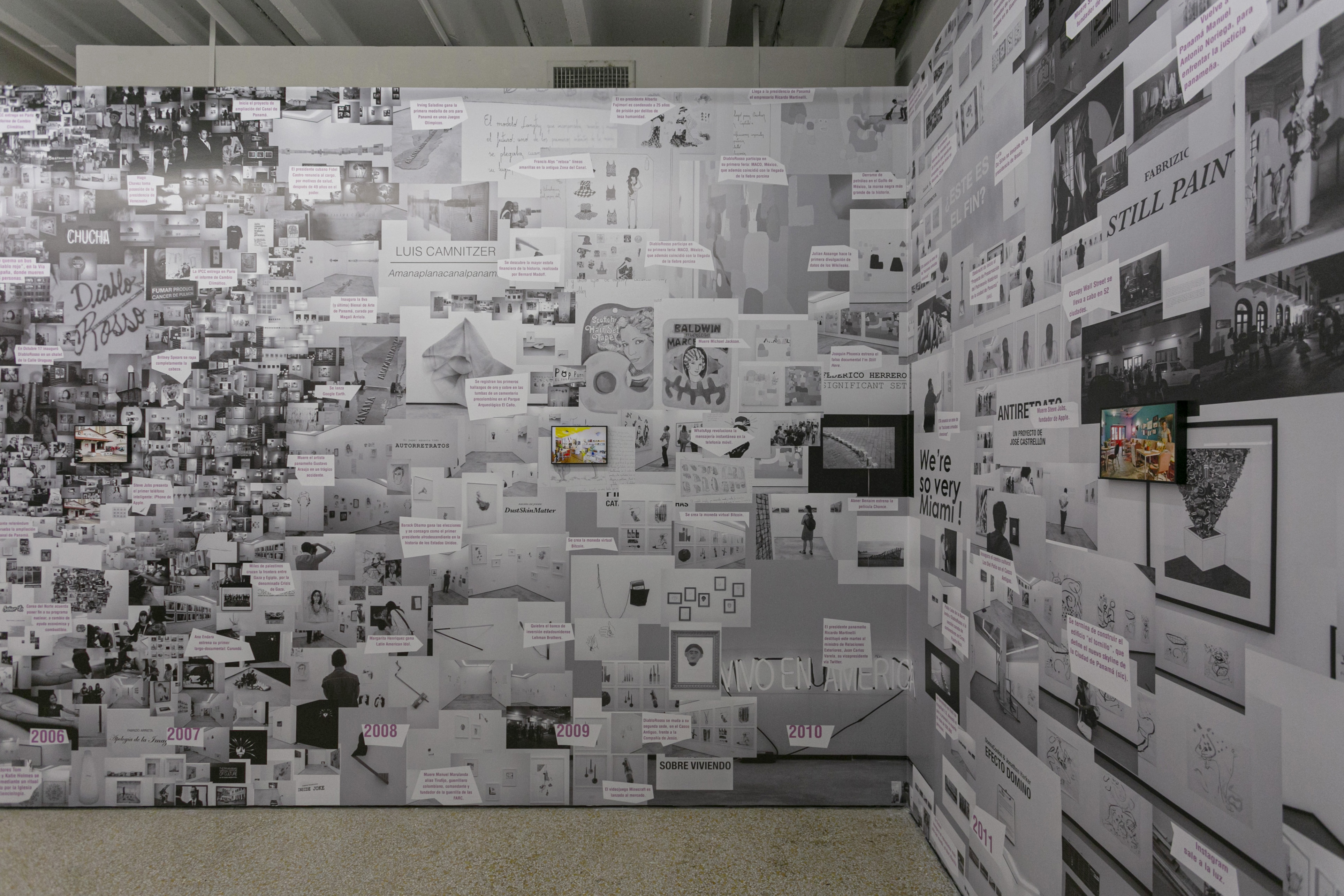

The main room of the gallery is complemented with the backspace, where a timeline of DiabloRosso’s history runs alongside that of the main artistic, political and social events of the past 15 years. Even though its presentation is formally different, the idea is to pay homage to the timelines shown by the US collective Group Material in their different exhibitions, and especially in Timeline: The Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America, exhibited at MoMA PS1 in New York, in 1984. The works in this room are in a dialog with Conlon and Harker’s 2017 video piece, The Voice Adrift, in which a message is put in a bottle that runs through various water currents until it finds a person to transmit the message to, and which to me comes as a perfect metaphor to understand the exhibition, the pieces contained in it as well as the work done by DiabloRosso and the “messages” that artists and exhibitions have sent each other over the last 15 years in history.

I wanted to finish with a few questions: What do you feel has been lacking or could’ve been different in these first 15 years? How do you imagine the next 15 years of Diablo Rosso? Do you think the project will still exist? Do you think it’ll keep transforming as it has done ever since its inception, or that it will have fulfilled its purpose at some point?

JW: Actually, it’s been a while since I have felt that the project had made its point. Not because it had reached its goal, but due to the indifference and lack of interest of the local audience. In 2017, before finding the gallery’s current space, I really considered not moving forward with the project. I felt that all these efforts didn’t make much of a difference, but when I found the space something changed, and more specifically the relationship with the audience shifted. This new location completely satisfies a personal interest of mine: to be able to reach a wider audience. Particularly an audience that doesn’t have access to art, and not by choice, but because of how far it is from their reality, especially in a country like Panama, with all its contrasts and limitations that you so accurately mentioned.

“If Muhammad doesn’t go to the mountain, the mountain goes to Muhammad” is the motto of this particular space, and this makes me very excited. This is precisely the excitement I feel every time that I work with an artist on a new exhibition project; or when developing an idea for a group show, and what it could mean for the audience thats sees it, for that person who walks past the space and to the most courageous among them, who actually walks in to see it more closely. To come closer to this audience, and to see the difference that art can make for them, is the reason why this project still exists, and why I keep putting just as much effort and work into it. That excitement keeps me in what could almost be a vicious cycle, which ends up preventing me from shutting the door for good, even though this project has always been hard to sustain financially.

There are plenty of things I’m sure I could’ve done better, but something that I feel I’ve been lacking most of all, is another person who could be a real support to the gallery’s management, in the same way that my team at SKETCH (the architecture firm that I founded the year that we opened DiabloRosso) has been supporting me. Without their commitment and understanding, I couldn’t devote as much time as I do to the gallery. Something that I did get right, though, was to define DiabloRosso a couple of years ago as a “commercial not-for-profit gallery”. This definitely removed the pressure of feeling that it should’ve worked as the business that it’s never really been. Diablo has a higher purpose, which is also a duality: on one hand, there is what we can bring to the place in which we find ourselves; and on the other, there are all the connections that we make out there, through the work we do with and for artists, which is the basic mission of any gallery. There is obviously a very potent synergy between both, which is what gives us strength to go on. I also have to admit that the gallery has allowed me to get acquainted with some of the most amazing people that I’ve ever had the chance to meet, having the greatest conversations and creating connections and relationships that I could’ve barely dreamed of had I not found myself in this world. In a nutshell, some of my closest friends I met through DiabloRosso, and this just makes all the hard work completely worth it.

You are a great weaver of networks, and in a distant, silent way, you’ve always helped us in some way or the other. I’m not only referring to Diablo Rosso, but also to all the spaces and artists who, at some point, were lucky enough to share moments with you. I’ve come to see that thanks to that, and to the effort of other key figures, there has been great development in the region. Thank you for all your work today and always, and for accepting the invitation and honoring us with the curatorship of this exhibition, which celebrates our teenage years together. Let’s hope these are but the first fifteen springs of many that we’ll be sharing in the future.

Una conversación entre Johann Wolfschoon y Pablo León de la Barra

PLB: Johann, quería que empezaras hablando de cómo comenzó la galería DiabloRosso, ¿Cómo surgió la idea de abrir una galería de arte contemporáneo en Panamá hace 15 años? ¿Habían otras galerías de arte en ese momento?

JW: Sinceramente, la intención inicial no fué la de crear una galería, DiabloRosso nació como un espacio que buscaba llenar algunos vacíos que nos hacían falta en Panamá, a cada uno de los cinco socios que fundamos el proyecto: Analida Galindo, Carlos Ucar, Miky Fábrega, Rafa Arrocha y yo. El proyecto se gestó principalmente como una tienda conceptual y café, con componente de cine independiente y galería. En la tienda podías encontrar desde moda vanguardista producida en Copenhagen, a elementos de diseño, joyería y/o decoración, tanto local como de todas partes del mundo. Era un “concept store” antes que estuviera de moda el término.

El café tenía un menú reducido pero maravilloso, diseñado por Clara Icaza, y con los mejores nombres para los platos que se han puesto en Panamá. En este espacio todos los martes proyectamos cine independiente, con una cuidadosa selección de películas. Esto lo hicimos por 8 años, sin fallar ni una semana. Cuando empezamos estas noches de “Cena-Cine” era muy difícil lograr tener público, pero a medida que fue pasando el tiempo, se volvió más regular, hasta el punto que si no reservabas, probablemente no encontrarías espacio para cenar. Esto es algo que nos ayudó a pensar que es posible formar públicos, lo cual nos ha dado energía para continuar con la galería hasta el día de hoy.

La galería nació dentro del café y era una parte integral de el. Vestía las paredes y, en algunas ocasiones, hasta modificaba su espacio. La visión de este espacio era mucho menos internacional que la del resto del proyecto. Principalmente buscaba ser una plataforma para los artistas locales, que sentíamos tenían el talento, pero no las oportunidades. Creamos un espacio modesto, con las condiciones básicas para exhibir, y allí mismo hicimos conciertos, fiestas, performances, conversatorios, etc etc...

En el 2006 en Panamá habían 3 galerías contemporáneas: Mateo Sariel, Allegro y Arteconsult, siendo esta última la que había sido históricamente más interesante. Su fundadora, Carmen Alemán, había vivido en Nueva York y tenía contactos y medios que le permitieron traer a Panamá algunos buenos artistas latinoamericanos. De estas tres, solamente Mateo Sariel continúa hoy operando.

PLB: ¿Cuál era el contexto artístico, pero también socio-político, en Panamá cuando abrió Diablo Rosso?

JW: En el 2006 cuando DiabloRosso inauguró, Panamá vivía un auge económico sin igual. Ese mismo año se hizo el referendum con el cual se aprobó la expansión del Canal de Panamá. El panorama era muy favorable y optimista para lanzarse al agua con un proyecto que, económicamente, no tenía ni pies ni cabeza. Nos encontrábamos a la mitad de un gobierno estable, con una economía en crecimiento y una fuerte inversión pública. Las tasas de desempleo se encontraban decreciendo, por lo cual la situación social era bastante tranquila. Este crecimiento lo vivimos hasta el 2014, cuando todo empezó a cambiar, principalmente por temas ligados a la corrupción estatal. Panamá siempre ha tenido un amplio espectro de multiculturalidad y diversidad de población por su carácter de tránsito. Pero también ha tenido problemas muy marcados en cuanto a la distribución de las riquezas y un pésimo sistema educativo, que solamente perpetúa la pobreza.

Para dar algo de contexto, en Panamá se llevaron a cabo algunas iniciativas que habían sido profundamente interesantes para la escena artística: De 1993 al 2002 se había publicado el suplemento Talingo (Adrienne Samos y Alberto Gualde) en La Prensa, el periódico de mayor circulación del país. Este llevaba artículos sobre arte, cine y cultura; La revista MOGO (2000-01), tenía una mirada fresca sobre la ciudad y sus dinámicas. Fundada por un grupo de artistas y diseñadores (Walo Araujo, Gustavo Araujo, Jonathan Harker, Miky Fábrega y Dany Silvera) proponía que “el Panamá oficial no es más que una mentira creída a base de tanto repetirse”; el Revolver (2000-03) de la mano de los diseñadores gráficos Peter Novey y Ricky Salterio, era un portafolio editorial muy visual y energético; además, en el 2003 ocurrió el la muestra Ciudad Múltiple, que tomaba la Ciudad de Panamá como espacio de exhibición. Codirigido por Adrienne Samos y Gerardo Mosquera, que fué absolutamente enriquecedor para la nueva generación de artistas y marcó la vida de quienes tuvieron la oportunidad de interactuar con el proyecto. Regularmente se realizaba también una Bienal de Arte, que había sido fundada como un concurso de pintura, pero cuya estructura se mantenía en constante evolución. Poco después de inaugurar DiabloRosso, se realizó el proceso y producción de la última de sus ediciones, curada por Magalí Arriola, bajo el tema: la Zona del Canal.

Realmente desde el principio de la década, al momento en que se funda el proyecto, en Panamá se había producido una desaceleración en lo referente al arte contemporáneo y la cultura en general. DiabloRosso más que buscar ser una respuesta a esto, esperaba convertirse en un canal que permitiera a una nueva generación, explorar nuevas ideas y caminos.

PLB: ¿Podrías hablar un poco de las primeras exposiciones? ¿Cómo fue la recepción de la galería en su contexto en ese momento?

JW: Inauguramos el espacio con la primera exposición de Cisco Merel en galería. Después de esto hicimos muchísimas muestras colectivas y open calls durante los primeros años, intercaladas con algunas individuales. Era un frenesí, en donde las exhibiciones cambiaban mensualmente. Yo tenía 26 años cuando inauguramos el espacio y cada uno de los socios teníamos mucha energía e ideas que poníamos sobre la mesa.

Localmente fué muy interesante. Inventamos exposiciones que no hacían mucho sentido e invitamos a artistas localmente consagrados a participar. Por ejemplo, hicimos una en la que a cada artista le dimos una tapa de inodoro de madera para que la utilizara como punto de partida para una obra (Dada-ístmo, 2007). Otra vez hicimos algo similar con sillas de madera (Sunny and Chair, 2008); y en otra ocasión a personalidades-intelectuales, les dimos cámaras desechables para que nos mostraran lo que veían (Show me yours: Tu lugar favorito, 2010). Hicimos convocatorias abiertas, con el papel como medio, para que el público fácilmente pudiera participar en el espacio. Los resultados eran siempre divertidos y las conversaciones que se gestaron fueron siempre muy enriquecedoras.

PLB: En algún momento Diablo Rosso empezó a mirar más allá de Panamá y a mostrar también artistas de fuera. ¿Cómo se dio ese proceso? ¿Cuáles fueron esos artistas? Recuerdo que nos conocimos alrededor de 2008, en aquel momento yo era director artístico de una galería en Londres y era parte del comité de galerías de la feria Maco en México y me escribiste un e-mail presentándome el proyecto de la galería.

JW: Nosotros nos conocimos en persona en el 2009 en el MACO de “la fiebre porcina”. Tu habías sido uno de los jurados que seleccionaban las galerías participantes en la sección de Nuevas Propuestas. Recuerdo que hicimos un booth pintado en color rosa, lleno de obras, la mayoría pintura, lo cual en ese momento en México era inimaginable (y probablemente la peor idea del mundo). Creo que la única otra pintura en toda la feria era un enorme Federico Herrero que tu mostrabas. Recuerdo que, haciendo gala de nuestros buenos modales, fuimos donde tu estabas y nos presentamos personalmente, y te agradecimos por habernos escogido. La verdad es que no recuerdo que hubiésemos conversado mucho, ni qué viste en lo que mostramos algo que pudiera interesarte (probablemente fueron las paredes rosa!), pero al año siguiente nos invitaste a participar en una sección que estabas curando en Circa, Puerto Rico. Nos invitaste junto con otras 5 galerías jóvenes ( en un proyecto que se llamó “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” donde participaron Proyectos Ultravioleta de Guatemala, Revólver de Lima, Proyectos Monclova y Preteen de Ciudad de México, y Beta-Local de Puerta Rico. Allí si nos conocimos, hablamos y hangeamos un montón y te debimos caer bien porque, aunque nuestro booth era aún peor que el de MACO, hemos seguido siendo amigos desde entonces.

Ese fue el momento en el que en DiabloRosso realmente empezamos a mirar hacia fuera. Los lazos que tejiste en esa feria y la camaradería que se dió, han sido la base para todo lo que hemos hecho, o tratado de hacer, de ese momento hacia adelante. Desde el 2012 las exhibiciones que realizamos empiezan a ser principalmente internacionales: La primera que hicimos fué junto a las chicas de La Central, que por temas de visado no habían podido participar en Circa. En esa muestra tuvimos a Federico Herrero, Pia Camil, Carolina Caycedo, entre otros. A inicios del año siguiente hicimos otra muestra curada por Emiliano Valdés, “Me asusta pero me gusta”, que se enfocaba principalmente en Guatemala, en donde participaba Stefan Benchoam, a quien también habíamos conocido en tu proyecto de Circa… Este tipo de dinámicas las repetimos bastante, sobre todo con Proyectos Ultravioleta, dirigida por Benchoam, con quien creamos una muy estrecha relación.

PLB: Lo que me interesaba en aquel momento cuando los invité a Puerto Rico, era que artistas y espacios de arte jóvenes del continente se conocieran y conectaran entre sí. Sabía que había muchas coincidencias de contextos culturales, urbanos y político-económicos, así como de compartir historias coloniales y modernas semejantes, sin embargo había en ese entonces un casi total desconocimiento unos de otros. El internet no era lo que es hoy, Facebook apenas iniciaba, no había Instagram, y por lo general todos mirábamos hacia Nueva York o Europa en vez de vernos a nosotros mismos. Creo que lo que sucedió después fue muy interesante, un proceso de intercambio, de conocernos y de aprender unos de los otros. Por la amistad que fuimos desarrollando, visité Panamá varias veces en los últimos años, la primera vez en Abril de 2010 vine por curiosidad porque quería conocer la ciudad donde DiabloRosso existía. Volví en enero de 2013 para dar una charla en la Bienal Centroamericana, BAVIC. Despues en noviembre de 2013 vine a visitar a Sandra Eleta en Portobello y a Donna Conlon y Jonathan Harker en Ciudad de Panamá, poco después adquiriendo su obra maestra ‘Drinking Song’ para la colección del museo Guggenheim en Nueva York. La última vez que estuve aquí fue en Agosto de 2017 para visitar a Sandra Eleta en relación a las fotos que ella había hecho de Ernesto Cardenal y Solentiname, que incluí en una exposición sobre Solentiname en NYU, en Nueva York y en el Museo Jumex en México. La verdad es que me hubiera gustado venir más veces, considerando la cantidad de veces que hago conexión en Panamá, algo que seguramente haría si Copa en ese entonces no cobrara más por hacer un stopover en Panamá. En todas estas visitas siempre me impresionó esa situación esquizofrénica de Panamá: por un lado la cantidad de rascacielos en construcción, lo que parecería indicar una economía acelerada; y por otro lado una especie de desierto cultural, donde si bien hay un Museo de la Biodiversidad, diseñado por Frank Gehry y un Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, este hasta hace poco se encontraba en un proceso casi de hibernación. Parecía que se construía mucho pero no se tenía claro que es lo que se quería construir, ni que la cultura es parte fundamental de la construcción de una sociedad madura. Panamá podría ser por su economía, localización y por ser un hub aéreo, un polo cultural importantisimo de la región y tener un museo a la altura de esto, sin embargo pareciera qué hay dinero pero no hay apoyo gubernamental o privado para las artes o la cultura. Con miedo a equivocarme pareciera también qué hay un vacío cultural, donde la generación anterior de artistas no ha sido capaz de acompañar a una posible nueva generación de artistas y activistas culturales. Tal vez estoy generalizando, pero Panamá tendría la capacidad de ser lo que otras ciudades estado como Dubai, Sharjah, Qatar o Singapur son para sus regiones, y tener una escena cultural, un museo o centro cultural, y/o una bienal a la altura de la ciudad. En este contexto resulta increíble que un proyecto como DiabloRosso haya conseguido existir y contribuir a su escena cultural por 15 años, y esto es algo que esta exposición celebra. En el caso de Centroamérica y el Caribe quizás es, junto con Proyectos Ultravioleta de Guatemala, un caso único. DiabloRosso ha contribuido en exhibir y crear conexiones entre artistas de Centroamérica y del resto del continente, de una manera que pocas galerías de las Americas lo han logrado. Como parte de la investigación hecha esta exposición también es evidente como el proyecto de DiabloRosso ha madurado a lo largo de estos 15 años. Esta exposición Quinceañere celebra estos primeros 15 años, mostrando obras de algunos artistas que han participado en construir la historia de DiabloRosso, pero también señalando algunas ausencias, sobre todo de artistas mujeres en un programa que ha sido predominsntemente masculino. Siento que a futuro sería importante también que DiabloRosso exhibiera también el trabajo de artistas de origen indígena e afro-descendientes (algo que además esta muy presente en la complejidad étnica y racial de Panamá) , algo que intentamos también incluir en esta muestra pero que por diferentes razones de logística al final no conseguimos hacer. La idea detrás de esta muestra era originalmente muy sencilla: invitar a 15 artistas, uno por año de vida, que en algún momento hubieran mostrado en la historia de DiabloRosso. Por la situación de pandemia y aislamiento que pasamos, me interesaba también que la exposición fuera una fiesta, y que en vez de usar el presupuesto de está en pagar transporte de obra, que el presupuesto se usara para invitar a estos 15 artistas a venir a Panama, y que cada une trajera consigo una obra como ‘regalo’ para esta celebración. Por la pandemia esto también resultó más complicado, las fronteras no terminaban de abrir, viajar tampoco era tan facil, y por lo mismo tampoco terminábamos de definir la fecha. Pensé también podríamos invitar entonces a que cada artista produjera una obra para el aniversario y que estas pudieran ser enviadas ‘dobladas’ por correo o FedEx, haciendo un guiño a las pinturas aeropostales de Eugenio Dittborn. Por tiempos en realidad tuvimos que trabajar con lo que teníamos, encontrar la forma de hacer llegar los trabajos a tiempo a Panama para la celebración de los quince años, y que los trabajos en conjunto crearán en la sala de exposición una suerte de cadáver exquisito, donde cada obra comunica las investigaciones estéticas de cada artista, pero donde también en conjunto crean entre ellas en el espacio de DiabloRosso un campo de energía que celebra la historia de la galería, pero que también dibuja posibilidades futuras de diálogo, acción y pensamiento para el futuro de la galería. La sala de la exposición también está pintada toda de rosa, esto quizás tiene que ver con mis primeros recuerdos del booth que vi de DiabloRosso en Zona Maco en México en 2009, o tal vez tiene que ver en que como no hablo italiano siempre pensé que rosso era rosa y no rojo, puede ser también como un homenaje a los pasteles y vestidos color rosa pastel de quinceañeras en sus celebraciones, o puede ser leido como una crítica institucional desde los tropicos al cubo blanco de exhibición, algo que siento DiabloRosso ha estado haciendo a lo largo de su historia. La sala principal de la galería se complementa con la sala posterior donde se incluye una línea de tiempo tanto de la historia de DiabloRosso así como del contexto artístico/político/social de estos últimos quince años. Aunque la presentación formalmente es diferente, la idea original era una especie de homenaje a las líneas de tiempo presentadas por el colectivo estadounidense Group Material en varias de sus exposiciones, especialmente en Timeline: The Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America, que presentaron en PS1 en Nueva York en 1984. Las obras de esta sala están en diálogo con un vídeo de Conlon y Harker, The Voice Adrift (La Voz a la Deriva) de 2017, donde un mensaje es enviado a través de una botella de plástico que navega a través de cuerpos de agua hasta encontrar una persona a quien transmitir ese mensaje, y que además me resulta una metáfora fundamental para entender la exposición y las obras, así como la labor que ha hecho DiabloRosso y los ‘mensajes’ que artistas y exposiciones han enviado a lo largo de estos quince años de historia.

Quería terminar con las siguientes preguntas: ¿Qué sientes que ha faltado o podría haber sido diferente en estos primeros 15 años? ¿Y cómo te imaginas los siguientes 15 años de DiabloRosso? ¿Crees que el proyecto seguirá existiendo? ¿Crees que se continuará transformando como lo ha hecho desde que nació? ¿O que más bien en algún momento cumplirá su ciclo de vida?

JW: Sinceramente hace unos años sentí que el proyecto ya había cumplido su ciclo. No porque hubiera logrado cumplir su meta, si no por la indiferencia y falta de interés del público local. En el 2017, antes de encontrar el espacio donde habitamos actualmente, realmente consideré no continuar más el proyecto. Sentía que no hacía mucha diferencia el esfuerzo; pero al encontrar este espacio algo cambió, especialmente la relación con el público cambió. Esta nueva ubicación satisface íntegramente un interés personal, que tiene que ver con poder llegar a un público más amplio. Específicamente a un público que no tiene acceso al arte, no por decisión, si no por lo alejado que está de su realidad, especialmente en un país como Panamá, con todos los contrastes y limitantes que acertadamente mencionas.

“Si Mahoma no va a la montaña, la montaña va a Mahoma” es el motto del espacio en el que nos encontramos, y esto me genera una emoción muy grande. Esa misma emoción la siento cada vez que pienso en una muestra que vamos a instalar, con las obras que presentará un artista; o el desarrollo de una idea de una muestra colectiva, y lo que eso puede llegar a significar para el público que lo ve, para esa persona que camina frente al espacio y para el más valiente que se anima a entrar y visitarlo de cerca. Llegarle a este público, y la diferencia que el arte puede hacer en él, es la razón por la que el proyecto sigue existiendo y por la que tanto esfuerzo y trabajo le invierto. Esa emoción me acaba manteniendo en un (quasi) círculo vicioso, que no me permite cerrar las puertas, aunque económicamente el proyecto siempre haya sido complicado de mantener.

Hay muchas cosas que estoy seguro hubiera podido haber hecho mejor, pero algo que realmente siento que me ha hecho mucha falta, es haber encontrado a una persona que sea un apoyo real en la dirección de la galería, de la misma manera que lo es mi equipo en SKETCH (la oficina de arquitectura que funde en el mismo año que inauguramos DiabloRosso), que sin su apoyo y comprensión, no le podría dedicar el tiempo que le dedico a la galería. Hay algo que si hice bien, y es el haber definido hace unos años a DiabloRosso como una “galería comercial sin fines de lucro”. Esto le quitó la presión de sentir que en algún momento debía funcionar como el “negocio” que nunca ha sido. Diablo tiene una misión mayor, que es además una dualidad: por un lado está lo que podemos aportar al lugar en el que estamos; y por el otro, son todas las conexiones que ocurren hacia afuera, con el trabajo que hacemos con y para los artistas. Obviamente existe una potentísima sinergía entre ambas, que es lo que nos da fortaleza. También tengo que aceptar que la galería me ha permitido conocer a las personas mas increibles que he conocido en mi vida, tener las conversaciones más ricas y crear lazos y conexiones con las que solamente hubiera podido soñar de no estar en este mundo. Es más, hoy en día varios de mis amigos más cercanos han sido gracias a DiabloRosso y creo que no hay mejor satisfacción que esto para el trabajo realizado.

Tu eres un gran tejedor de redes y, desde la distancia y en silencio, siempre nos has ayudado de una manera u otra. No me refiero solamente a DiabloRosso, si no a todos los espacios y artistas que de alguna u otra manera hemos tenido la dicha de compartir contigo. Yo veo que gracias a esto, y al esfuerzo de algunas otras figuras clave, ha habido un gran crecimiento en la región. Gracias por todo tu esfuerzo hoy y siempre, y gracias por aceptar la invitación y honrarnos con la curaduría de esta exposición, que celebra una adolescencia juntos. Esperemos que sea la primera de muchas quince-primaveras que podamos compartir.

PLB: ¡Más sabe el diable por rosa que por viejo!

¡Larga vida al DiablxRossx!

Tuesday - Saturday

1-6pm

Sunday

11- 4pm

Closed Monday

1-6pm

Sunday

11- 4pm

Closed Monday