DONNA CONLON

No Stone Unturnedcurated by Jens Hoffman

solo exhibition

ene 25 - mayo 02 / 2020

ene 25 - mayo 02 / 2020

Photos: Rapha Salazar

OBSERVACIONES CON EL MUNDO

Jens Hoffmann

Central American art is not necessarily on the radar of many international museums, curators, or collectors outside the region. Even curators specialising in art from Latin America often skip Central America’s seven countries, focusing their research on Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, or more recently Peru. But this does not mean that art is not thriving in the countries between Mexico and Colombia; it is just not as visible outside the region. The reasons are several. The museum and gallery infrastructure is still developing; a serious collector base is still nascent; arts education mostly remains in its infancy; there is not much connection among the different countries that would lend itself to meaningful networks; and transportation between the capital cities is just as expensive as it would be to fly to Bogotá, Mexico City, or even New York or Los Angeles, all of which offer wider overviews of contemporary art production and museums with world-class collections.

Nevertheless, a closer look reveals quite a different, albeit more localised, reality. Diablo Rosso, Panama’s premier gallery for contemporary art, has for almost fifteen years pushed the envelope when it comes to the presentation of art from Central America and the wider Latin American region and recently upped their game, moving into a new and larger space that in its versatility and size can easily compete with spaces in London or Berlin. Diablo Rosso has been instrumental in establishing and nurturing the careers of a number of Central and Latin American artists, including that of US-born and Panama-based Donna Conlon, who is now opening No Stone Unturned, her first solo exhibition at the gallery.

Conlon was born in Atlanta and grew up in Texas, where she lived until graduating from college. In 1994 she moved to Panama for the first time. She went back to the States for an MFA at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, then decamped back to Panama and has considered the country her home ever since. Her family background is partly Latin American, which certainly helps to explain her affection for this part of the Americas. Conlon undertook graduate studies in biology at the University of Kansas, originally intending to complete a PhD. Yet she ultimately left that world, unable to shake her doubts about academic life—teaching, research, publishing papers. Yet her science studies strongly influence her artistic methodologies, which are based on research and observation, often involving procedures that would be at home in the fields of archaeology or anthropology. Conlon worked for a time as a research assistant to a botanist and as a biology lab technician at Cornell University, where she took free classes in scientific illustration as well as courses in sculpture, all of which likewise had an enormous impact on her artistic work.

Conlon operates in a number of media, yet film and video are her main focus. Most of her films have a pared-down aesthetic—a no-fuss yet elegant documentary minimalism that on occasion offers poetic moments and sequences. One of her main concerns has been the relation between the natural world outside urban areas and humanity’s impact on those spaces. Human-made trash has been a recurring object for study: she collects it, categorizes it, and used it early in her career to create assemblages.

Yet Conlon eventually found this alone unsatisfactory, sensing that once objects are removed from their native context, something important—their aura, as Walter Benjamin phrased it—evaporates. A crucial shift occurred when she began to document collections of objects, initially plastic straws, in situ with a video camera. Out of this emerged her first film, Cleanup (2000), a two-channel piece presenting her collecting hundreds of straws and simultaneously putting the straws back in similar places. The artist remarks, “After this, the video camera became a tool of preference. It was so powerful to be able to direct the viewer’s gaze and attention via the lens. It enabled me to figure out how to show what I was seeing. I was finally seeing a way to think and question and communicate through art, which was what I so badly wanted to do.”

In the early film Country Road (2002), Conlon walks along a road in Maine (she was doing a residency at Skowhegan) collecting garbage people have flung from their cars. The trash is not immediately visible at first—mostly hidden in high grass or behind bushes—and it is astonishing to discover how much junk lies in a seemingly clean place. The artist places each object in the middle of the road, right on the line, forming a mile-long sculpture (visually related to the British artist Richard Long’s line works) of human-produced and -disposed waste: beer cans, buckets, bottles, cigarette packages, car mats, sandwich wrappers, cardboard boxes, coffee cups, pieces of carpet. Conlon is not only speaking about the environmental impact of trash on nature, but also using useless, worthless items to paint a subtle portrait of a consumer culture whose ecological impacts are hidden in plain sight, should we only observe the world more astutely. The video Natural Refuge (2003) continues the focus on trash, but this time the artist investigates what the garbage itself is hiding and how nature in some way capitalises on waste. We see her picking up pieces of garbage and turning them over to reveal the life underneath: worms, beetles, ants.

The early films objectively document situations that have a mostly negative impact on the environment and offer portraits of consumer behaviour. Yet none makes an overt statement about what is harmful to nature and is to be avoided. There is no preaching about saving the world—simply observations that invite us to draw our own conclusions. Another film highlighting the plastic crisis is Más me dan (They Give Me More, 2005). Here we see Conlon removing one plastic bag from yet another plastic bag from yet another plastic bag from yet another plastic bag, for more than five minutes. In 2006 Conlon began to collaborate with artist Jonathan Harker on a number of films following similar territory. In Summer Breeze (2007) we see a typical metal fence, shot from a single camera angle, swaying in the wind, little by little collecting trash that forms a colourful quasi-sculpture.1

Conlon’s early work also includes a film about the rapidly changing skyline of Panama City, which by now features hundreds of high-rise buildings, practically rivalling Dubai or Doha. In Urban Phantoms (2004) we are first introduced to the city’s impressive skyline; thereafter, little by little, via stop-motion animation, another skyline gradually builds in front of the existing one using colourful found trash. The actual skyline thus drowns in a heap of waste.

Lately Conlon has developed a fascination with the work of the German explorer, geographer, naturalist, and philosopher Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), one of the first Europeans to travel the Americas extensively for modern scientific purposes. Humboldt published his findings in a major series of volumes and was notably—as early as 1800—the first person to mention human-induced climate change, based on his research in Latin America. Humboldt’s research was distinct from that of his peers because he observed plants and animals in context, not in isolation, and was thus equipped to speculate on the “unity of nature.” Conlon is specifically fascinated with Humboldt’s achievements as an illustrator and cartographer (recall her early exposure to scientific illustration at Cornell). His drawn works were intended to stimulate the mind—to “speak to the senses,” as he put it. One of his most famous scientific illustrations was of the Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador.

Conlon’s practice unites biology and art, archaeology and anthropology. The artist understands herself first and foremost as an observer, not an activist—a term and practice she reports feeling uncomfortable with. Looking at her films closely and repeatedly, one discovers an almost compulsive curiosity and a deep longing to compare and analyse objects within the larger framework of humanity and nature. Conlon finds profound meaning in the seemingly ordinary detritus of civilisation, which in her hands becomes more than simply evidence of what was produced and used, then discarded. She describes her work as “like finding pottery shards in an archaeological dig. The only difference is that an object I find on the street or something I see in my environment is evidence of a lifestyle of living human beings rather than dead ones. Like pottery shards, bits of trash form a part of a larger picture that can be understood bit by bit. As with an archaeological find, there is also an inherent beauty in a chunk of faded red plastic. I’m using the example of garbage, but it applies to the other things, too.”

It is undeniable, however, that Conlon’s work is not simply objective scientific research. It is an excavation of the remains of a civilisation of conspicuous consumption, standing on the verge of ecological apocalypse. Viewing the work invites personal reflection, and of course speculation on the personal experiences and opinions of its maker. Conlon believes that art, indeed because it is never entirely objective and allows for humour, poetry, beauty, or rhythms, always prompts reflection and identification, and thus has a better chance to communicate with the public than scientific reports. One can see parallels to the work of other Latin American artists such as Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, Oscar Muñoz, Rivane Neuenschwander, or Francis Alÿs. All, in very different ways and particular formations, are observers, working in ways that are poetic and political, never didactic, and never just black or white.

The exhibition No Stone Unturned connects Conlon’s film and video practice to her work in other media that she has mastered with equal virtuosity. During the first and last week of the exhibition, the gallery will present screenings of her entire body of film and video works. The presentation will also feature “Notas de Video” (Video Notes), a program of films by other contemporary Latin American film artists whose work contextualises Conlon’s.

The drawings titled Ropes and Mangroves (2017–20) depict what happens to mangroves in the time between low and high tide, when all kinds of trash get stuck in the plants. The simple black-and-white drawings focus in particular on ropes that wrap themselves around the mangroves in a snakelike fashion.

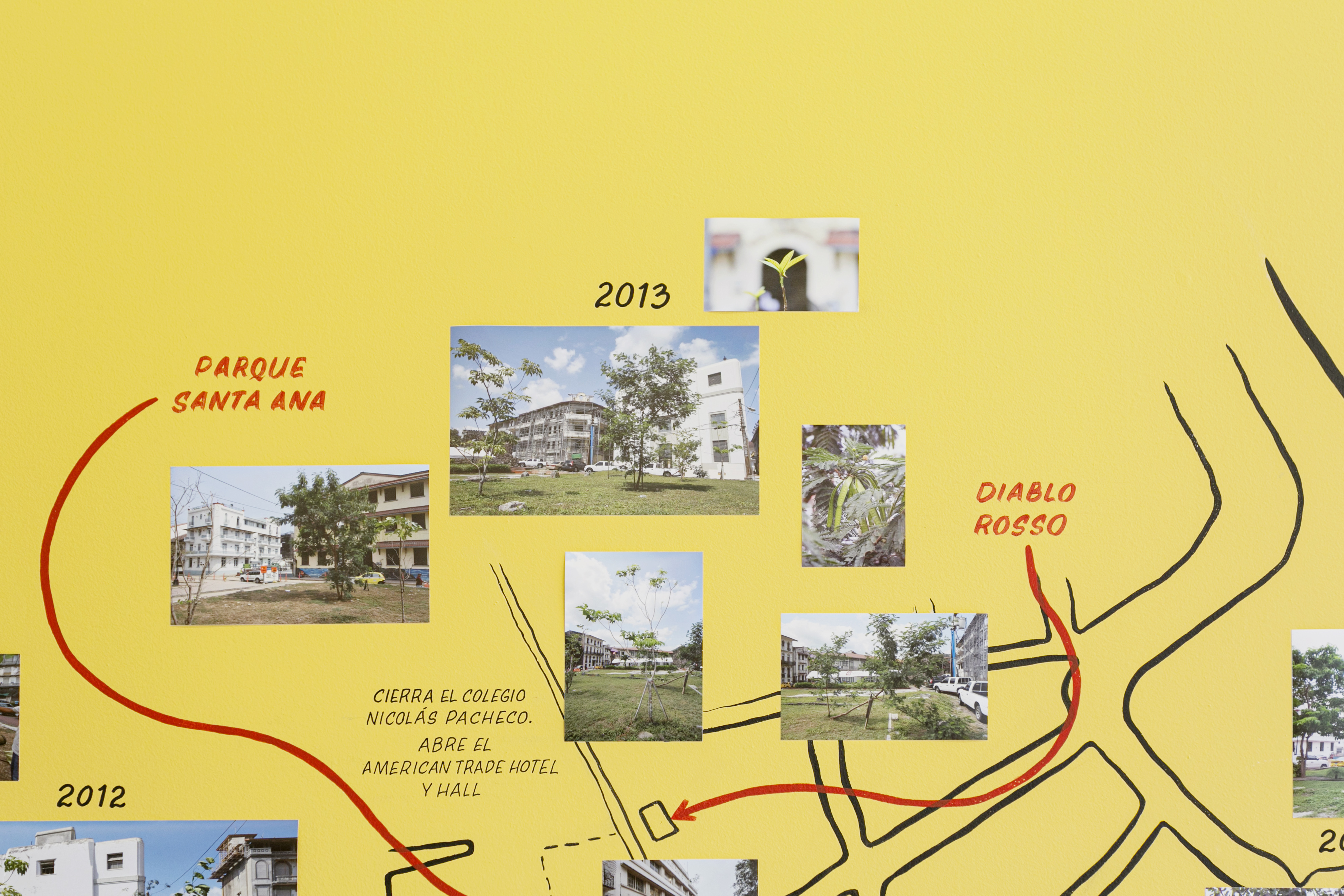

Raices is a site-specific work in the old quarter of Panama City in which Conlon has reforested a vacant lot with endemic tree species following the precise protocols of Smithsonian reforestation projects. As a result of the enormous real-estate boom in Panama City, nature is not valued in urban areas and every available sliver of land is urbanised. “Real estate” in Spanish is bienes raices (literally “good roots,” while a bien is also a property or a belonging), hence the title Raices, with its double meaning. The presentation in the gallery will involve maps, documentation of the growth of the trees, objects found on the lot, and directions to the square (a three-minute walk from the gallery) so that visitors can see the project firsthand. This small forest will eventually be cut down, like all the others, for the sake of so-called development, and it has become a focal point for a small group of anti-gentrification activists.

The central work in the exhibition is the film Desde las cenizas (From the Ashes, 2019), which centers on a hummingbird. Conlon’s undergraduate thesis project involved woodpeckers, and she spent a lot of time with ornithologists, including helping out with a bird-banding project: she caught birds in specialised nets, attached uniquely numbered bands to their legs, recorded species, gender, age, and other data, and then released them. To put the band on, one lays the bird in one hand on its back and attaches the little metal bracelet with the other hand. Often the birds do not fly away immediately thereafter but continue to rest in the scientist’s hand, as if they are sleeping or faking their death, then suddenly jump up and fly away. Conlon captured such a moment on video, in close-up, with a hummingbird using a high-speed camera (1,500 frames per second). Conlon was not particular at first about what bird species she wanted to film, but then realised that hummingbirds would be particularly good for this exercise when she learned that the Aztecs believed they are reborn warriors: the “phoenix of the Aztecs.”

Conlon consulted with various scientists and went to a forest in Gamboa, Panama, for the film’s shooting. On screen we see the hummingbird’s brightly coloured feathers, the claws, the beak, then the blink of the eye that triggers the moment of “awakening” and departure from the artist’s hand. It all seems like a visual haiku—a short poem created with images and sound rather than words. Sounds added after the final edit include a subtle, abstract rumble and a wind-like noise that seem full of anticipation, and a different, high-pitched sound that evokes tension. Then when the hummingbird revives and moves its eye, the nondiegetic sound goes silent, and the actual sound of the forest enters.

At the risk of oversimplifying the film’s message, it is tempting to perceive a parallel being drawn to a certain unconscious state humanity finds itself in at this moment in history. Conlon may not call herself an activist, but she certainly aspires to stimulate an awakening, a collective enlightenment, as to our species’ precarious status, teetering on the brink of extinction.

Note

1. Their collaboration will be the subject of an overview show in Panama in 2021, and in tandem with this first solo survey will offer further insight into Conlon’s unique practice.

OBSERVACIONES CON EL MUNDO Jens Hoffmann

El arte centroamericano no está en el radar de muchos museos, curadores o coleccionistas fuera de la región. Incluso, los curadores especializados en arte de América Latina, a menudo se saltan los siete países de Centroamérica, centrando su investigación en Colombia, México, Brasil, Argentina o, más recientemente, Perú. Pero esto no significa que el arte no esté prosperando en los países entre México y Colombia; simplemente no es tan visible fuera de la región. Las razones son varias. La infraestructura de museos y galerías aún se está desarrollando; una base sólida de coleccionismo aún es incipiente; la educación artística permanece principalmente en una etapa emergente; no hay mucha conexión entre los diferentes países que se prestarían a la creación de redes significativas; y el transporte entre las ciudades capitales es tan costoso como volar a Bogotá, Ciudad de México o incluso Nueva York o Los Ángeles, todos los cuales ofrecen una visión más amplia de la producción de arte contemporáneo y poseen museos con colecciones de clase mundial.

Sin embargo, una mirada más cercana revela una realidad bastante diferente, aunque de carácter más local. Diablo Rosso, la principal galería de arte contemporáneo de Panamá, durante casi quince años ha estado a la vanguardia cuando se trata de la presentación de arte de América Central y la región latinoamericana en general y recientemente mejora su oferta, mudándose a un espacio nuevo y más grande que en su versatilidad y tamaño pueden competir fácilmente con espacios en Londres o Berlín. Diablo Rosso ha sido fundamental para establecer y fomentar las carreras de varios artistas centroamericanos y latinoamericanos, incluída la de Donna Conlon, nacida en Estados Unidos y radicada Panamá, que ahora inaugura No Stone Unturned, su primera exposición individual en la galería.

Conlon nació en Atlanta y creció en Texas, donde vivió hasta graduarse de la universidad. En 1994 se mudó a Panamá por primera vez. Regresó a los Estados Unidos para obtener un MFA en el Maryland Institute College of Art en Baltimore, luego regresó a Panamá y ha considerado el país como su hogar desde entonces. Su origen familiar es en parte latinoamericano, lo que sin duda ayuda a explicar su afecto por esta parte de las Américas. Conlon realizó estudios de posgrado en biología en la Universidad de Kansas, originalmente con la intención de completar un doctorado. Sin embargo, finalmente abandonó ese mundo, incapaz de sacudir sus dudas sobre la vida académica: enseñar, investigar, publicar. No obstante, sus estudios en ciencias influyen fuertemente en sus metodologías artísticas, basadas en la investigación y la observación, que a menudo implican procedimientos que serían comunes en los campos de la arqueología o la antropología. Conlon trabajó durante un tiempo como asistente de investigación para un botánico y como técnico de laboratorio de biología en la Universidad de Cornell, donde tomó clases gratuitas de ilustración científica y cursos de escultura, todo lo cual también tuvo un enorme impacto en su trabajo artístico.

Conlon opera en varios medios, sin embargo, el video es su enfoque principal. La mayoría de sus videos tienen una estética reducida, un minimalismo documental sencillo pero elegante, que en ocasiones ofrece momentos y secuencias poéticas. Una de sus principales preocupaciones ha sido la relación entre el mundo natural fuera de las áreas urbanas y el impacto de la humanidad en esos espacios. La basura producida por el ser humano ha sido objeto recurrente de estudio: ella la recoge, la clasifica y la utiliza, desde el principio de su carrera, para crear ensamblajes.

Conlon finalmente encontró esta práctica insuficiente, sintiendo que una vez que los objetos se eliminan de su contexto natural, algo importante, su aura, —como lo expresó Walter Benjamin—, se evapora. Un cambio crucial ocurrió cuando ella comenzó a documentar colecciones de objetos, inicialmente carrizos de plástico, in situ, con una cámara de video. De esto surgió su primer video Cleanup (2000), una pieza de dos canales que la presenta recolectando cientos de carrizos y simultáneamente colocando los carrizos en lugares similares. La artista comenta: “Después de esto, la cámara de video se convirtió en una herramienta de preferencia. Fue tan poderoso poder dirigir la mirada y la atención del espectador a través del lente. Me permitió descubrir cómo mostrar lo que estaba viendo. Finalmente estaba viendo una manera de pensar, cuestionar y comunicarme a través del arte, que era lo que tenía muchas ganas de hacer ".

En uno de sus primeros trabajos, Country Road (2002), Conlon camina por una carretera en Maine (estaba haciendo una residencia en Skowhegan) recogiendo basura que la gente arrojó de sus autos. Al principio, la basura no es visible de inmediato, principalmente oculta en la hierba o detrás de los arbustos, y es sorprendente descubrir cuánta basura hay en un lugar aparentemente limpio. La artista coloca cada objeto en el medio del camino, justo en la línea, formando una escultura de una milla de largo (visualmente relacionada con las obras en línea del artista británico Richard Long) de desechos producidos y deshechados por humanos: latas de cerveza, cubos, botellas, paquetes de cigarrillos, alfombras de autos, envoltorios de sándwich, cajas de cartón, tazas de café, piezas de alfombra. Conlon no solo habla sobre el impacto ambiental de la basura en la naturaleza, sino que también usa elementos útiles e inútiles para pintar un sutil retrato de una cultura de consumo cuyos impactos ecológicos están ocultos a simple vista, si solo observamos el mundo con más astucia. El video Natural Refuge (2003) continúa enfocándose en la basura, pero esta vez la artista investiga qué esconde la basura y cómo la naturaleza de alguna manera aprovecha los desechos. La vemos recogiendo pedazos de basura y dándoles la vuelta para revelar la vida debajo: gusanos, escarabajos, hormigas.

Los primeros trabajos documentan objetivamente situaciones que tienen un impacto principalmente negativo en el medio ambiente y ofrecen retratos del comportamiento del consumidor. Sin embargo, ninguno hace una declaración abierta sobre lo que es perjudicial para la naturaleza y qué debe evitarse. No se predica sobre como salvar al mundo, simplemente observaciones que nos invitan a sacar nuestras propias conclusiones. Otro video que destaca la crisis del plástico es Más me dan (They Give Me More, 2005). Aquí vemos a Conlon retirando una bolsa de plástico de otra bolsa de plástico de otra bolsa de plástico de otra bolsa de plástico, durante más de cinco minutos. En 2006, Conlon comenzó a colaborar con el artista Jonathan Harker en varias videos que siguen una trayectoria similar. En Summer Breeze (2007) vemos una cerca de metal típica, tomada desde el ángulo de una sola cámara, meciéndose en el viento, recogiendo poco a poco la basura que forma una colorida cuasi escultura.**

Sus primeros trabajos también incluyen un video sobre el horizonte urbano rápidamente cambiante de la ciudad de Panamá, que ahora presenta cientos de edificios de gran altura, prácticamente rivalizando con Dubai o Doha. En Urban Phantoms (2004) nos presenta por primera vez el impresionante horizonte de la ciudad; luego, poco a poco, a través de la animación stop-motion, otro horizonte se construye gradualmente frente al existente utilizando colorida basura encontrada. El horizonte real se ahoga en un montón de basura.

Últimamente, Conlon ha desarrollado una fascinación por el trabajo del explorador, geógrafo, naturalista y filósofo alemán Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), uno de los primeros europeos en viajar por las Américas con fines científicos modernos. Humboldt publicó sus hallazgos en una importante serie de volúmenes y fue notablemente, ya en 1800, la primera persona en mencionar el cambio climático inducido por el hombre, según su investigación en América Latina. La investigación de Humboldt fue distinta de la de sus compañeros, porque observó plantas y animales en contexto, no de forma aislada, y por lo tanto estaba equipado para especular sobre la "unidad de la naturaleza". Conlon está específicamente fascinada con los logros de Humboldt como ilustrador y cartógrafo (recuerde su exposición temprana a la ilustración científica en Cornell). Sus dibujos estaban destinados a estimular la mente, a "hablar con los sentidos", como él lo expresó. Una de sus ilustraciones científicas más famosas fue sobre el volcán Chimborazo en Ecuador.

La práctica de Conlon une biología y arte, arqueología y antropología. La artista se entiende a sí misma ante todo como una observadora, no como una activista, un término y una práctica con la que se siente incómoda. Al mirar sus videos de cerca y repetidamente, uno descubre una curiosidad casi compulsiva y un profundo anhelo de comparar y analizar objetos dentro del marco más amplio de la humanidad y la naturaleza. Conlon encuentra un significado profundo en los detritos aparentemente ordinarios de la civilización, que en sus manos se convierte en algo más que una simple evidencia de lo que fue producido y utilizado, y luego desechado. Ella describe su trabajo "como encontrar fragmentos de cerámica en una excavación arqueológica. La única diferencia es que "un objeto que encuentro en la calle o algo que veo en mi entorno es evidencia de un estilo de vida de seres humanos vivos en lugar de muertos. Al igual que los fragmentos de cerámica, los trozos de basura forman parte de una imagen más grande que se puede entender poco a poco. Al igual que con un hallazgo arqueológico, también hay una belleza inherente en un trozo de plástico rojo desteñido. Estoy usando el ejemplo de la basura, pero también se aplica a las otras cosas ".

Sin embargo, es innegable que el trabajo de Conlon no es simplemente una investigación científica objetiva. Es una excavación de los restos de una civilización de consumo conspicuo, al borde del apocalipsis ecológico. Contemplar su trabajo invita a la reflexión personal y, por supuesto, a la especulación sobre las experiencias y opiniones personales de su creadora. Conlon cree en el arte, de hecho porque nunca es enteramente objetivo y permite el humor, la poesía, la belleza o los ritmos, siempre provoca reflexión e identificación, y por lo tanto tiene una mejor oportunidad de comunicarse con el público que los informes científicos. Se pueden ver paralelismos con el trabajo de otros artistas latinoamericanos como Jennifer Allora y Guillermo Calzadilla, Oscar Muñoz, Rivane Neuenschwander o Francis Alÿs. Todos, de maneras muy diferentes y desde formaciones particulares, son observadores, que trabajan de manera tanto poética como política, nunca didáctica y nunca solo “blanco o negro”.

La exposición No Stone Unturned conecta la práctica de video de Conlon con su trabajo en otros medios, el cual ha dominado con igual virtuosismo. Durante la primera semana de la exposición, la galería presentará proyecciones de todo su cuerpo de obras en video. La muestra también presentará “Notas de video”, un programa de videos de otros artistas latinoamericanos contemporáneos cuyo trabajo contextualiza el de Conlon.

Los dibujos titulados Ropes and Mangroves (2017-2020) muestran lo que les sucede a los manglares en el tiempo entre la marea alta y la baja, cuando todo tipo de basura se atasca en las plantas. Estos simple dibujos en blanco y negro se centran particularmente en las cuerdas que se envuelven alrededor de los manglares en forma de serpiente.

Raíces es un trabajo “site-specific” en el Casco Antiguo de la ciudad de Panamá, en el que Conlon ha reforestado un lote vacante con especies de árboles endémicos, siguiendo los protocolos precisos de los proyectos de reforestación del Smithsonian. Como resultado del enorme auge inmobiliario en la ciudad de Panamá, la naturaleza no se valora en las zonas urbanas y se urbaniza cada franja de tierra disponible. "Bienes inmuebles" en español son bienes raíces (literalmente "buenas raíces", mientras que un bien también es una propiedad o una pertenencia), de ahí el título Raíces, con su doble significado. La presentación en la galería incluirá mapas, documentación del crecimiento de los árboles, objetos encontrados en el lote y direcciones hacia la plaza (a tres minutos a pie de la galería) para que los visitantes puedan ver el proyecto de primera mano. Este pequeño bosque eventualmente será talado, como todos los demás, en aras del llamado desarrollo, y se ha convertido en un punto focal para un pequeño grupo de activistas contra la gentrificación.

El trabajo central de la exhibición es el video Desde las cenizas (From the Ashes, 2019), que se centra en un colibrí. El proyecto de tesis de pregrado de Conlon involucró pájaros carpinteros, y pasó mucho tiempo con ornitólogos, incluyendo el trabajo en un proyecto de anillamiento de aves: atrapó aves en redes especializadas, colocó bandas con números únicos a sus patas, registró especies, su género, edad y otros datos, para luego liberarlas. Para colocarles la banda, uno pone el pájaro en una mano sobre su espalda y sujeta la pequeña pulsera de metal con la otra mano. A menudo, las aves no vuelan inmediatamente después, sino que continúan descansando en la mano del científico, como si estuvieran durmiendo o fingiendo su muerte, y de repente saltan y vuelan. Conlon capturó ese momento en video, en primer plano, con un colibrí usando una cámara de alta velocidad (1,500 cuadros por segundo). Al principio, Conlon no prestaba mayor atención a qué especie de ave quería filmar, pero luego cayo en cuenta de que los colibríes serían particularmente buenos para este ejercicio cuando se enteró de que los aztecas creían que eran guerreros renacidos: el "ave fénix de los aztecas".

Conlon consultó con varios científicos y fue a un bosque en Gamboa, Panamá, para el rodaje del video. En la pantalla vemos las plumas de colores brillantes del colibrí, las garras, el pico, luego el parpadeo del ojo que desencadena el momento del "despertar" y la salida de la mano de la artista. Todo parece un haiku visual: un poema corto creado con imágenes y sonido en lugar de palabras. Los sonidos agregados después de la edición final incluyen un retumbar sutil y abstracto, y un ruido similar al viento que parece estar lleno de anticipación, y un sonido diferente y agudo que evoca tensión. Luego, cuando el colibrí revive y mueve su ojo, el sonido no diegético se silencia y entra el sonido real del bosque.

A riesgo de simplificar demasiado el mensaje del video, es tentador percibir un paralelismo atraído por un cierto estado inconsciente en el que se encuentra la humanidad en este momento de la historia. Puede que Conlon no se llame activista, pero ciertamente aspira a estimular un despertar, una iluminación colectiva, en cuanto al estado precario de nuestra especie, al borde de la extinción.

Nota 1.

Su colaboración será el tema de una exhibición en Panamá en 2021, y en conjunto con esta primera muestra individual ofrecerá una visión más profunda de la práctica única de Conlon.

Tuesday - Saturday

1-6pm

Sunday

11- 4pm

Closed Monday

1-6pm

Sunday

11- 4pm

Closed Monday